Sprawl.

Is sprawl like pornography? Speaking of the latter in 1964, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said, “I know it when I see it,” even though it might be difficult to articulate in words.

Not that sprawl, whether in an urban or suburban setting, hasn’t been defined.

“The term sprawl, as used by land developers, planners and governmental institutions, critically describes a pattern of low-density, often unsightly, automobile-dependent development that has been a common form of growth outside of urban areas since at least World War II,” according to Cornell University.

The ying to sprawl’s yang is smart growth.

Again, Cornell University defines smart growth with 10 different components:

- Mixed land uses;

- Takes advantage of compact building design;

- Creates a range of housing opportunities and choices;

- Creates walkable neighborhoods;

- Fosters distinctive, attractive communities with a strong sense of place;

- Preserves open space, farmland, natural beauty and critical environmental areas;

- Strengthens and directs development toward existing communities;

- Provides a variety of transportation choices;

- Makes development decisions predictable, fair and cost effective;

- Encourages community and stakeholder collaboration in development decisions.

So the difference between sprawl and smart growth would seem to be apparent.

But as with defining pornography, what constitutes sprawl is not so simple. In Denver, giant Stapleton is the biggest example of the blurry line between sprawl and smart, sustainable growth.

Central Park Station One would be one of the largest transit-oriented developments in the metro area when it opens in Stapleton. It this TOD enough to convince skeptics that Stapleton is an example of smart growtn and not sprawl?

Last month, I wrote a column regarding the upcoming sale of Forest City, the real estate investment trust that is the master developer of Stapleton, which has been described as the largest infill development in the U.S.

In the column, I wrote how a dozen years ago, Jon Ratner, the vice president of sustainability for Forest City, described Stapleton as the antithesis of sprawl.

Niccolo Casewit, a Denver native and an architect, couldn’t disagree more with Ratner.

“I can’t believe Stapleton is touted as “urban infill”; and of course it’s sprawl – Northfield is a big set of boxes and the new neighborhoods the most car-dependent in Denver – that’s why I-70 is being expanded, for one. Not much of a Denver legacy, but for its sheer size, Stapleton as it’s built out-impinges on Quebec, and Monaco Boulevard with so much traffic it’s often impassable,” Casewit wrote on my Facebook page.

Even the Denver Post, on a Facebook promo for an article about Stapleton soon reaching build-out as far as single-family home construction, had this to say: “While many argue that Denver doesn’t need another development as sprawling (my emphasis) as Stapleton, it’s worth noting that the city’s supply of single-family lots is about to run out.”

Well, since Stapleton is the site of a former international airport and covers 4,700 acres, it doesn’t seem likely that Denver (or many other places in the country, for that matter) has to worry about a master-planned community as large as Stapleton appearing on its doorstep.

And while The Shops at Northfield Stapleton certainly includes big-box retailers, does that mean Stapleton is an example of sprawl? After all, retail follows rooftops and there are plenty of rooftops in Stapleton and surrounding neighborhoods. Would it be better for the environment if Stapleton residents had to drive farther to find a SuperTarget or Bass Pro?

Stapleton has won numerous awards for sustainability and smart growth, yet some still consider it a prime example of sprawl in Denver.

And last year, Forest City Real Estate Trust unveiled plans for Central Park Station One, which would be one of the largest transit-oriented developments in the Denver metro area. Central Park Station One would be a 4 million-square-foot mixed-use development at Central Park Station. It would include a 190,000-sf Class AA mixed-use office building, a 300-unit apartment community, a 120-unit condominium development and 60,000 sf of retail space, all integrated around an expansive public plaza

Tom Gleason, the longtime spokesman for Forest City Stapleton, doesn’t think Stapleton is sprawl.

Gleason said Stapleton is “definitely an example of smart growth,” and noted that the community had received a number of national and international awards for its sustainability, including the Development Award from the Stockholm Partnership.

The Urban Land Institute once used a drawing of Stapleton to illustrate a paper titled Ten Principles for Smart Growth on the Suburban Fringe.

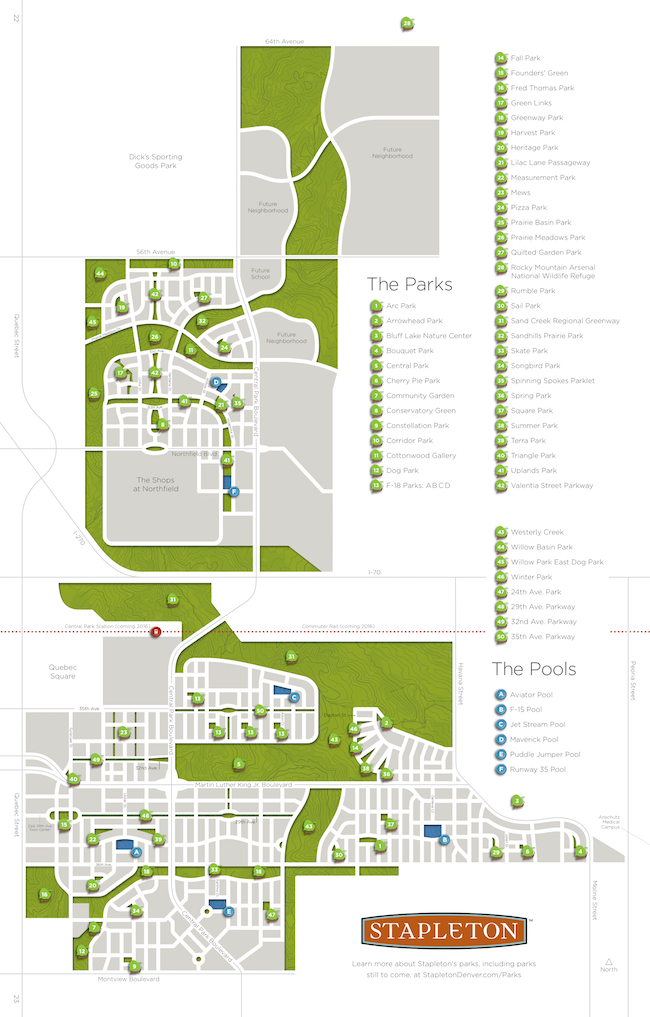

“More importantly, there are 22,000 people who apparently disagree with the person who wrote to you,” said Gleason. “Those Stapleton residents have chosen to live at Stapleton because of its expansive system of parks, its energy-efficient housing in a variety of price points and its excellent schools— just to name a few of the highlights of Denver’s success in growing from within.”

Gleason’s perspective is supported by another national report.

“Stapleton illustrates a range of choices that’s missing in a lot of new developments,” according to a report by the Smart Growth Network publication produced by a cooperative agreement between the International City/County Management Association and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“The Stapleton neighborhood has a wide variety of homes at different prices, so that everyone from a receptionist to a CEO can live in the same neighborhood,” the Smart Growth Network continued. “There are apartments for retirees and people with lower incomes, as well as town-houses and single-family homes. Some residents live close enough to their jobs to walk to work, and many children can walk to school.”

Stapleton has more than 1,100 acres of parks and open space, yet some equate Stapleton with sprawl.

On the other hand, Avery Lajeurnesse, in an undergraduate honor thesis at the University of Colorado at Boulder, concluded that Stapleton is more sprawl that New Urbanism.

Lajeurnesse analyzed Stapleton, Riverfront Park and Highland Garden Village in Northwest Denver in a thesis published in 2016 titled: “Urban Juxtaposition: A Precedent Analysis of New Urbanism in Denver, Colorado,” for an environmental design program at CU.

“The Stapleton neighborhood, the largest greyfield development in the country, lacks many New Urbanist principles in its implementation; primarily related to land use patterns, residential density, and transportation,” Lajeurnesse wrote in his paper.

As part of his research, he took an hour-long bus ride to Stapleton and then spent another hours walking around the development at a “leisurely pace.”

This is how he described his experience: “On a beautiful Saturday, I saw a total of 25 other pedestrians walking throughout the neighborhood. The monotony of the repetitive architecture and streetscaping as well as the lack of pedestrian infrastructure provided me with a less-than-pleasant walking experience.”

He said Stapleton has the lowest walkability score of Highland Garden Village or Riverfront Park. Of course, both Highland Garden and Riverfront Park are a fraction of the size of Stapleton.

“Stapleton takes up an extremely large amount of land with minimal density,” Lajeurnesse wrote, describing the community as “auto-centric.”

So should have Forest City developed Stapleton into a more dense and compact development, with even more open space? Are the 1,116 acres of parks at Stapleton not enough?

There seems little appetite for density in Denver, given how many neighbors protest many proposed five-story apartment buildings.

“Density is great, but only to the extent that it actually connects people to their daily needs,” and, “Density for density’s sake will be detrimental to the livability of Denver,” architect Casewit, who believes Stapleton is an example of sprawl, recently posted on Facebook.

Let me know if you think Stapleton is sprawl or an example of smart growth? And what are other examples of either sprawl or smart growth in the metro area? If I receive enough responses and insights, I will write another column on the topic. I can be reached at jrchook@gmail.com.

Meanwhile, vote in the poll below on whether you think Stapleton is an example of sprawl or Smart Growth.